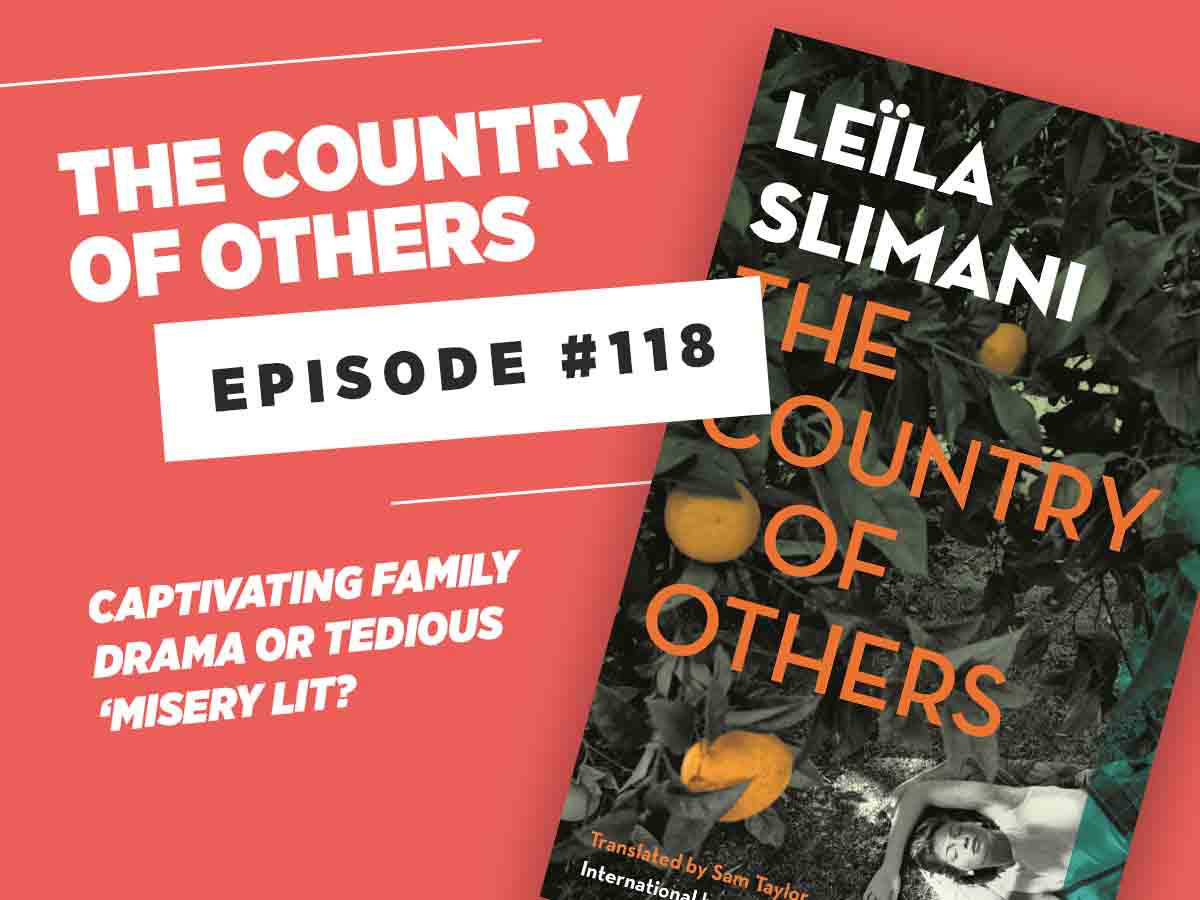

Join us as we deep-dive into Ferrante-esque family saga The Country of Others by Leïla Slimani. Critics and fellow authors have been impressed: Salman Rushdie called it ‘an exceptional novel’ while Claire Messud ‘didn’t want it to end’ but what did Laura’s book club make of The Country of Others (translated into English by Sam Taylor), the first book in a planned trilogy.

1944. After the Liberation, Mathilde leaves France to join her husband in Morocco.

But life here is unrecognisable to this brave and passionate young woman. Her life is now that of a farmer’s wife – with all the sacrifices and vexations that brings. Suffocated by the heat, by her loneliness on the farm and by the mistrust she inspires as a foreigner, Mathilde grows increasingly restless.

As Morocco’s struggle for independence intensifies, Mathilde and her husband find themselves caught in the crossfire.

In this episode we were delighted to be joined by regular listener Youssra, who gave us her Moroccan perspective on the book, and opened our eyes to some of the debate around issues of colonialism and European feminism.

Listened to the episode? Want to share your thoughts? Have you read this or other books by Leïla Slimani? Click to jump down to the comments and let us know your views, we love to hear from you.

Book recommendations

Une année chez les francais by Fouad Laroui One of our guest Youssra’s absolute favourite reads, one that she wishes was translated into English but sadly for us Anglais it only currently exists in French. Should you be able to read it, the book is a lightly fictionalised memoir telling the story of Mehdi, a ten-year-old boy from a small village in the Atlas mountains who arrives in Casablanca to attend a French school. With warmth and charm Laroui examines the culture shock and micro-aggressions from his French tutors while creating a hugely enjoyable cast of characters. Youssra would say ‘a must-read’.

Une année chez les francais by Fouad Laroui One of our guest Youssra’s absolute favourite reads, one that she wishes was translated into English but sadly for us Anglais it only currently exists in French. Should you be able to read it, the book is a lightly fictionalised memoir telling the story of Mehdi, a ten-year-old boy from a small village in the Atlas mountains who arrives in Casablanca to attend a French school. With warmth and charm Laroui examines the culture shock and micro-aggressions from his French tutors while creating a hugely enjoyable cast of characters. Youssra would say ‘a must-read’.

The Moor’s Account by Leila Lalami Youssra’s second pick from a Moroccan writer, and this one available in English. In this Booker longlisted and Pulitzer Prize shortlisted novel, Laïla Lalami imagines the memoirs of Mustafa al-Zamori, called Estebanico, a real-life individual who with his Spanish master and two other Spaniards was shipwrecked and then marooned in the New World. ‘As he journeys across America with his Spanish companions, the Old World roles of slave and master fall away, and Estebanico remakes himself as an equal, a healer, and a remarkable storyteller.’ His Moroccan identity meant that while the other three Spaniards were widely celebrated for their survival Estebanico was only mentioned in a footnote. Today he is believed by many to have been the first African explorer of North America and is consequently feted as a figure of historical significance, but at the time, his skin colour and his status ensured his silence. In The Moor’s Account Youssra says, ‘Lalami has given him his voice back.’

The Moor’s Account by Leila Lalami Youssra’s second pick from a Moroccan writer, and this one available in English. In this Booker longlisted and Pulitzer Prize shortlisted novel, Laïla Lalami imagines the memoirs of Mustafa al-Zamori, called Estebanico, a real-life individual who with his Spanish master and two other Spaniards was shipwrecked and then marooned in the New World. ‘As he journeys across America with his Spanish companions, the Old World roles of slave and master fall away, and Estebanico remakes himself as an equal, a healer, and a remarkable storyteller.’ His Moroccan identity meant that while the other three Spaniards were widely celebrated for their survival Estebanico was only mentioned in a footnote. Today he is believed by many to have been the first African explorer of North America and is consequently feted as a figure of historical significance, but at the time, his skin colour and his status ensured his silence. In The Moor’s Account Youssra says, ‘Lalami has given him his voice back.’

This Blinding Absence of Light by Tahar Ben Jelloun A Youssra recommendation that Laura followed up on. ‘Crafting real life events into narrative fiction, Ben Jelloun reveals the horrific story of the desert concentration camps in which King Hassan II of Morocco held his political enemies in underground cells with no light and only enough food and water to keep them lingering on the edge of death. Working closely with one of the survivors, Ben Jelloun narrates the story in the simplest of language and delivers a shocking novel that explores both the limitlessness of inhumanity and the impossible endurance of the human will.’ Laura thought it would be a tough read but found it a surprising page-turner, full of insight and wisdom about humanity in extremis.

This Blinding Absence of Light by Tahar Ben Jelloun A Youssra recommendation that Laura followed up on. ‘Crafting real life events into narrative fiction, Ben Jelloun reveals the horrific story of the desert concentration camps in which King Hassan II of Morocco held his political enemies in underground cells with no light and only enough food and water to keep them lingering on the edge of death. Working closely with one of the survivors, Ben Jelloun narrates the story in the simplest of language and delivers a shocking novel that explores both the limitlessness of inhumanity and the impossible endurance of the human will.’ Laura thought it would be a tough read but found it a surprising page-turner, full of insight and wisdom about humanity in extremis.

All Men Want to Know by Nina Bouraoui A sideways leap, but a delightful one for Kate, who discovered All Men Want To Know in her local Little Free Library one day. The author is French-Algerian and like Slimani lived in her native country until her teens before moving to France. In this work of auto fiction she traces her memories of her Algerian childhood, contrasting them with her experiences in contemporary Paris where she is visiting bars and trying to claim her identity as a homosexual woman. Writer Ninen Govinden describes it as ‘a resolutely queer novel of female sexual identity, of remembering and becoming, trauma, mothers and daughters, colonialism and finding a way through.’ It’s offbeat, surprising and enjoyable – highly recommended.

All Men Want to Know by Nina Bouraoui A sideways leap, but a delightful one for Kate, who discovered All Men Want To Know in her local Little Free Library one day. The author is French-Algerian and like Slimani lived in her native country until her teens before moving to France. In this work of auto fiction she traces her memories of her Algerian childhood, contrasting them with her experiences in contemporary Paris where she is visiting bars and trying to claim her identity as a homosexual woman. Writer Ninen Govinden describes it as ‘a resolutely queer novel of female sexual identity, of remembering and becoming, trauma, mothers and daughters, colonialism and finding a way through.’ It’s offbeat, surprising and enjoyable – highly recommended.

Year of the Elephant by Leila Abouzeid First published in Arabic in Morocco in 1983, this novel almost immediately sold out. It is one of the first Moroccan novels written in Arabic to be translated into English. ‘In this moving fictional treatment of a Muslim woman’s life, a personal and family crisis impells the heroine to reexamine traditional cultural attitudes toward women. Cast out and divorced by her husband, she finds herself in a strange new world. Both obstacles and support systems change as she actively participates in the struggle for Moroccan independence from France. This feminist novel is a literary statement in a modern realist style. Many novels by women of the Middle East that have been translated reflect Western views, values, and education. By contrast, “Year of the Elephant” is uniquely Moroccan and emerges from North African Islamic culture itself. Its subtle juxtaposition of past and present, of immediate thought and triggered memory, reflects the heroine’s interior conflict between tradition and modern demands.’

Year of the Elephant by Leila Abouzeid First published in Arabic in Morocco in 1983, this novel almost immediately sold out. It is one of the first Moroccan novels written in Arabic to be translated into English. ‘In this moving fictional treatment of a Muslim woman’s life, a personal and family crisis impells the heroine to reexamine traditional cultural attitudes toward women. Cast out and divorced by her husband, she finds herself in a strange new world. Both obstacles and support systems change as she actively participates in the struggle for Moroccan independence from France. This feminist novel is a literary statement in a modern realist style. Many novels by women of the Middle East that have been translated reflect Western views, values, and education. By contrast, “Year of the Elephant” is uniquely Moroccan and emerges from North African Islamic culture itself. Its subtle juxtaposition of past and present, of immediate thought and triggered memory, reflects the heroine’s interior conflict between tradition and modern demands.’

Notes

The Words Without Borders article referenced by Kate in the episode: “You Belong Nowhere”: Leïla Slimani on the Trauma of Colonialism and Her Forthcoming Novel

An interesting article from Hespress, Morocco’s leading online news website: Colonial undertones in Leïla Slimani’s book put her under fire.

Can’t wait for the next book by Leïla Slimani? Get out your French dictionary...

If you enjoyed the discussion don’t miss our episode on Leïla Slimani’s previous book Lullaby

Transcript: Episode #118: The Country of Others by Leïla Slimani

Kate 0:09

Hello, and welcome to the Book Club Review. I’m Kate.

Laura 0:12

I’m Laura.

Kate 0:13

And this is the podcast about book clubs and the books that get people talking.

Laura 0:17

Today we’re discussing the country of others by Leïla Slimani. It’s the first of a planned trilogy telling the story of one French Moroccan family. It’s been translated from the original French into English by Sam Taylor, and it’s the latest book read by my book club.

Kate 0:32

Leïla Slimani is a French Moroccan author, whose previous novels have been highly successful. Her first Adèle is about a woman addicted to illicit sexual encounters. She then wrote Chanson Douce or Lullaby which won her international acclaim and the prestigious Prix Goncourt in France, and made for a fabulous book discussion, as you’ll hear if you go back into our archive and listen to episode 30. Her next book Sex and Lies is a non-fiction investigation into the sex lives of Moroccan women. Slimani has also been busy as French president Emmanuel Macron’s a personal representative for promoting French language and culture.

Laura 1:08

Her latest book has been described by The Times as ‘a panoramic ambitious tale’, while author Salman Rushdie found it ‘exceptional’. What though did my book club make of it? Did we love it or loathe it? And was it a good book club read?

Kate 1:23

Keep listening to find out here on The Book Club Review.

Kate 1:30

Book club! It feels like it has been so long!

Laura 1:34

It has been a while! We have to get back to our roots.

Kate 1:37

I know, our roots. So I can’t wait to get into this. How did your book club come to choose this one?

Laura 1:42

It was me, it was me, Kate. I saw Leïla Slimani’s latest book, which I would note is called In the Country of Others in the North American market. I saw it at the library and was really intrigued but wasn’t sure I was going to read it by myself. You mentioned this in the intro, but my book club read and discussed Lullaby, Slimani’s kind of breakthrough novel in English. My book club really loved Lullaby – I think that’s true – whereas I vehemently disliked it. So I was intrigued to see what we would make of this one, knowing of course, as you do that I am a big fan of historical novels.

Kate 2:20

Yes, I listened to that episode this morning, actually. And you’re absolutely right. You were the real outlier. And you complained because even our guest, Chloe Dunbar, and I were also relentlessly positive. And I think you felt a little bit … I think bullied was the word you used.

Laura 2:37

Did I? Oh, I’m not usually such a shrinking violet! I’m usually up for a fight.

Kate 2:41

But this is a very different book, isn’t it? Tell us what it’s about?

Laura 2:45

Well, it’s not a family memoir, but it is a novel inspired by Leïla Slimani’s own family history. Her grandmother was a French war-bride who married a Moroccan man and went and settled in Morocco in the post-war period. We’ll get to that. You know, how much of this is based on her true family history? How much is fictionalised? But just looking at the blurb this is how it’s described there. ‘After World War Two Mathilde leaves France from Morocco to be with her husband, whom she met while he was fighting for the French army. A spirited young woman, she now finds herself a farmer’s wife, her vitality sapped by the isolation, the harsh climate and the mistrust she inspires as a foreigner, but she refuses to be subjugated or confined to her role as a mother of a growing family. As tensions mount between the Moroccans and the French colonists Mathilde’s fierce desire for autonomy parallels her adopted country’s fight for independence in this lush and transporting novel about race, resilience and women’s empowerment. Is that the same blurb that you have because I don’t like that. I don’t think that’s an accurate description of the novel.

Kate 3:48

[Laughs] I wasn’t actually really listening to the words you were saying. I was just listening to your voice thinking ‘oh, that’s nice to hear Laura’s voice.’

Laura 3:58

I have her rapt attention, listeners…

Kate 3:59

We haven’t spoken in a little while so I’m really sorry, I can’t answer to that.

Laura 4:03

What does your blurb say? Does it talk about a spirited young woman and Mathilde’s fierce desire for autonomy paralleling her adoptive country’s fight?

Kate 4:11

No, it doesn’t. Okay, all right. So, ‘Alsace, 1944. Mathilde finds herself falling deeply in love with Amine Belhaj, a Moroccan soldier billeted in her town fighting for the French. After the liberation Mathilde leaves her country to follow her new husband to Morocco, but life here is unrecognisable to this brave and passionate young woman. suffocated by the heat of the Moroccan climate, her loneliness on the farm, by the mistrust she inspires as a foreigner and by their lack of money. Mathilde grows restless as violent threatens and Morocco’s own struggle for independence grows daily, Mathilde and Amine’s refusal to take sides sees them and their family at odds with their own desire for freedom. How can Mathilde, a woman whose life is dominated by the decisions of men, hold her family together in a world that’s being torn apart?

Laura 4:59

That is quite different. I think it’s much better. You won’t know what the differences are. But listeners and I do. And I think what’s interesting there is just the focus on Mathilde and this this idea that it’s all about her desire for autonomy, whereas actually I read it a lot more as a partnership between Mathilde and Amine, and their quite dysfunctional, but at heart loving relationship, a sort of battle against the elements and the forces that are opposed to them as they try to carve out a life together.

Kate 5:28

Well, let’s discuss, but first we have a clip. The audiobook is published by Faber & Faber, read by Nebiha Akkari.

Nebiha Akkari 5:38

She had felt the same dismay when she first landed in Rabat on the first of March 1946, despite the desperately blue sky, despite the joy of seeing her husband again and the pride of having escaped her fate, she was afraid. It had taken her two days to get there. from hospital to Paris, from Paris to Marseille, then from Marseille to Algiers, where she boarded an old junkers and thought she was going to die. Sitting on a hot bench among men with eyes wearied from years of war, she’d struggled not to scream. During the flight, she wept, vomited prayed. In her mouth, she tasted the mingled flavours of bile and salt. She was sad, not so much at the idea of dying above Africa, as at appearing on the dock to meet the love of her life in a wrinkled vomit-stained dress. At last she landed safe and sound. And Amine was there more handsome than ever, under a sky so profoundly blue that it looked as though it had been washed in the sea.

Nebiha Akkari 6:55

Her husband kissed her on both cheeks, aware of the other passengers watching him. He siezed her right arm in a way that was simultaneously sensual and threatening. He seemed to want to control her. They took a taxi and Mathilde was finally able to nestle close to Amine’s body to feel his desire, his hunger for her. ‘We are staying in the hotel tonight’, he told the driver and as if trying to defend his morality added ‘This is my wife.’

Kate 8:43

For me, Mathilde was the character that I was invested in, the character that I cared about – or so I thought, but then one of the things I really admired about the book is the way that Slimani seemingly effortlessly does flip from character to character. And so sometimes you’re in Amine’s head and you’re getting his perspective. And sometimes you’re in Aïcha’s – they have two children, Aïcha and Selim. And Aïcha is, what, sort of 5, 6, 7, throughout the course of this book?

Laura 9:08

I think she’s probably 10. By the end.

Kate 9:10

It’s roughly her early childhood, her formative years, would you say?

Laura 9:14

Yeah, and I think the reason we’re being vague is because the timeline of this book is so brilliantly done, use the word effortless. And this novel feels effortless. I don’t usually love novels that cover so much ground, it’s fair to say we’ve roughly got 10–15 years here.

Kate 9:33

Yes, I think it’s 10. I think I read the each novel in this trilogy was going to be around 10 years.

Laura 9:38

And what she does though, is that whole years can pass in a paragraph or two, and then she’ll just sort of zoom in on the present moment, one present moment with such a vivid depiction that it pulls together this wider narrative arc and I don’t know how she does it. It was effortless, and I thought her style had changed dramatically from Lullaby – and maybe that’s a translation thing. I’m not sure if they were done by the same translator?

Kate 10:03

I think they were, I think Sam Taylor is Slimani’s English translator.

Laura 10:07

So maybe Slimani is adopting or evolving into a slightly different literary style for this subject matter.

Kate 10:14

And that’s a moment to say I think it’s a wonderful translation. You know, sometimes with translated books, there’s just something about the syntax of the sentence or there’s something which slightly jolts you out and makes you think, ‘Oh, I remember I’m reading a translated book.’ But there was never a moment of that with this. The writing just flows. It’s so vivid, it’s so powerful, and I think credit to this excellent translation. But I was gonna say that’s interesting, because for me, I almost felt she’s such a pacey writer, you know, her books have this momentum, you feel like you’re careering through a story, certainly Lullaby, the story about the nanny that kills the two children, had this really explosive structure where it starts with this incredibly dramatic event. And then the rest of the novel is a kind of whydunnit. And it’s one where I certainly sat and compulsively read that in one go. This is very different, particularly when you know it’s going to be a trilogy. And so there is a sense of a slower pace, but actually, I felt it could have been longer. And I would have loved it to be longer. I almost felt like she wasn’t giving herself enough time to really develop these characters. And I was really interested to read an interview with her where she talks about how she grew up reading the French classics. She really admired these long Russian and French family sagas. And she said, ‘and I asked myself, would I be able to write such a book one day after Lullaby, after the Prix Goncourt, I wanted a really challenging project.’ And so yeah, I love that this is a trilogy, but there was almost something a little bit of a sense of skating through, and I would have loved it if it had just settled even more.

Laura 11:47

Good thing. There’s going to be another two books then.

Kate 11:49

There’s a lot of drama isn’t there, from the moment that Mathilde arrives. And one of the other interesting things that I’ve read – Slimani talked about how her novels are about disillusionment: Lullaby was about the disillusionment of the idea of motherhood, or parenthood. This is about the idea of Mathilde’s disillusionment, because she thinks she’s going off to this … but she doesn’t really have any idea about the country that she’s going off to! She has almost the kind of idea it’s going to be like a fairy story or something. And then the reality when she gets there, from the very beginning, when she and her husband, Amine, are travelling to this land that he owns, this farm, where they’re going to live in the countryside, and they’re travelling on a sort of horse-drawn cart, and the driver is whipping the horse to make it go more quickly. And she beggs him not to and reaches out, and he threatens to turn the whip on her. So from the very beginning, you see all those illusions and her naiveté, it all comes crashing down on her that that moment, you’re like, ‘oh, no,’ you know, ‘how is she going to survive?’

Laura 12:46

She is an incredibly realised character. And she’s also an incredibly flawed character. And so I felt quite a lot of impatience with her at moments as I’ve started to reread it, while equally understanding that she is very young. I think she’s only twenty when she arrives, Amine is twenty-eight. As you say, she’s naive. And not only that, she aspires to a beautiful lifestyle, like what she sees on the film screens. And so there’s this huge gap between her expectations of her life and the reality she’s living. And at the same time, I felt a little bit of sympathy with Amine, who is like, ‘look, this is our life together. This is what we’ve chosen. My mother never cried. You’re crying every single moment of the day.’ I guess I had sympathy for both of them. I also wanted Mathilde to toughen up a little,

Kate 13:32

But then she does, I think. One of the things I think Slimani does really brilliantly is that her characters aren’t straightforwardly likeable or dislikable, they have moments where you like them. They have moments where you root for them, they have moments where you feel like they’re doing the right thing. And then they have moments where they behave really badly and you feel really depressed. And she takes you into their inner thoughts so you understand why they might be behaving the way that they do. With Mathilde’s husband, Amine, he is a Moroccan man, but he has served with the French army. He’s now going back to Morocco and in France, he is a Moroccan man in Morocco he is a colonised man, and Slimani wrote about how that comes with a certain amount of humiliation. And as a result of that humiliation, he becomes violent himself and then visits that violence on Mathilde and his family, but you understand or she’s trying to explore I think, where it’s coming from, which is why it’s so interesting.

Laura 14:28

Every key player in this novel is somehow subjugated or confined in their role. It’s not as simple as just women are subjugated as you flag Amine is very subjugated and disempowered in his role and trying to navigate his identity as a Moroccan man, as an independent farmer, as a father, a husband to a white French woman, and then his own experience having been in the French army.

Kate 14:51

It’s also this wider political context, which is very alive, very active, it affects the dynamics of everything hugely, which is the French colonists who are there who are farming, who at this point in time, have the status, have the power, have the support of the government?

Laura 15:07

No, well they are the government. This is important to say.

Kate 15:10

And then Amine, you know, Moroccan men, who are trying to make their way. And so Amin is frustrated, because he is not getting the support, he’s not getting the government loans. He’s sort of ostracised to a certain degree. I mean, it was quite an interesting experience reading about this, because on the one hand, she writes about it all so vividly. And so you feel the emotion of what’s happening. But intellectually, as an outsider, and someone who doesn’t know much about the history of Morocco, doesn’t know much about the history of the French colonisation of Morocco. I found myself a bit at sea. And I did a couple of times stop and go to the internet to look up Moroccan history. Because I thought I don’t quite understand the context of this, I’m not clear about the power dynamics and what’s going on, because it’s at the moment when Morocco was starting to fight for independence. But we haven’t quite got there yet. So this is the early rumblings of that. And then I’m guessing the French retaliation. Right?

Laura 16:16

Oh, interesting. You’ve done more immediate reading than me.

Kate 16:18

Well, that’s interesting that you’re looking even more vague than me. Because one of the things I think, is just read this book, without knowing anything, I don’t think you need to know about this history in order to enjoy this book for what it is, which is this incredibly vivid, powerful family story. But it’s interesting that it seemed almost slightly strange to me that you don’t get more context, but perhaps it’s because she’s writing for an audience who know this.

Laura 16:43

But what we should say and I think this is a good segue is that there is a risk when we read novels and think we are getting a full picture. I do this too. We’re all armchair travellers through novels, right? And I love a novel. I love a historical novel. I love a novel about another culture. And in some ways, I do tend to think, ‘Aha, I now have a better understanding of that culture or that period in time.’ And I was racing through this novel quite uncritically, because of the paceyness of of her writing and the drama that she injects throughout. And I posted on Instagram, just saying, you know, ‘I’m loving this’ really quickly on the story. And someone reached out to me, someone by the name of Youssra, who is Moroccan-British. And it was a simple message. She just said, ‘most Moroccans who read it agree that Leïla Slimani is a colonialism apologist. Her take on a difficult period in the country’s history is a bit controversial, to put it mildly.’ And that’s all she said. And I was just like, ‘Oh, oh! Tell me more.’ And listeners, we were able to reach out to Youssra and talk to her in some depth about her view of The Country of Others. And just give us a different perspective.

Kate 17:55

Well that sounds like a good moment, then to listen to a little bit of that chat that we had with her. It went on for over half an hour, Laura and I could easily have sat and chatted to her for an hour and a half. And Youssra, I’m so sorry, but just for time, obviously, we’ve just had to clip out bits here and there. But let’s hear a little bit of that conversation where she began by telling us a little bit about herself.

Youssra 18:16

My name is Youssra. I’m Moroccan British. I live in England. Have been living here for 11 years now. I love reading I have a passion for books. I have a bachelors in French literature and a master’s degree in language and communication in English. I love reading in French, Arabic and English as well. I have a real passion for international literature. That’s about me.

Kate 18:39

So which language then did you read The Country of Others in seeing as you have so many options?

Youssra 18:45

I’ll be honest, I looked in Kindle and the French version was a bit more expensive than the English version. So I went for the English version. This is the first time I’ve read Leïla Slimani in English. Usually I read her books in French. But this time I read it in English.

Kate 19:02

And would it have been translated, then, into Arabic? Is there an Arabic version?

Youssra 19:05

Not that I know of. To be honest, most Moroccan writers who write in other languages do not really bother translating into Arabic simply because Moroccan readership is very diverse and most people read in French. We are mostly a bilingual country.

Laura 19:21

That makes me curious what language Moroccan literary heavyweights are writing, are they writing in Arabic? Or are they choosing to write in French?

Youssra 19:28

Lately, there’s more writers writing in Arabic. But the first prominent writers were writing in French, the likes of Driss Chraïbi, Tahar Ben Jelloun, they were celebrated in France and in Morocco, and they’ve had a French education. So naturally, they brought in French but they are very much celebrated in Morocco as well. But we noticed more and more Moroccan authors born and bred in Morocco with a Moroccan education who choose to write in Arabic, not just Arabic, in Moroccan Arabic. Which is, not to make things complicated for you, is a little bit different from classical Arabic that you would find in other Arab countries.

Kate 20:08

And so for Laura and me and for our book clubs, this is a novel that we’re reading very much in terms of narrative and plot, and she writes these incredibly vivid characters, and it’s a family story that you get very drawn into. Definitely, as an outsider, you’re very aware of the sense of the different cultures and this idea of a colony, a colonial country. But I feel like to a Moroccan reader, there’s clearly a whole range of layers and nuances that we are not alive to. So I think what Laura and I are really curious about how this book sits with you, how it impacted you when you read it.

Youssra 20:42

I mean, in terms of style, I’ll give it to you. She writes beautifully, but to me, it’s style over substance, basically. I found this very flawed, and extremely detrimental to Moroccans. It is supposed to be a multi-voiced or multi-point-of-viewed novel, because it’s not just about Mathilde, all the other characters are given a voice. So I was expecting to have a more of a balance. But I didn’t find that. It was very much colonist’s account of that period of the history of Morocco. It was even more painful for me because I am from the same city where all the events happened. I am from Meknes. So I knew every little street detail she talked about, I know it. I grew up there, even the school where Aïcha used to go, I used to borrow books from that school. It felt like okay, this is my city, this is my country. But the characters, no, I didn’t identify with them. I didn’t relate to them. And I didn’t even like them, they didn’t make sense to me. It was just too much for me in terms of clichés and stereotypes. Men are bloodthirsty, they’re violent, they are ignorant. Women are sensual, but brainless. I mean, even the food – she hated on the food! I draw a line there. You can disparage Moroccan men as much as you like, I’ll turn a blind eye, but Moroccan food, no, sorry, you can’t do that. Leave Moroccan food alone, and Moroccan women as well, you know, women of that period in the 50s. They were so full of optimism, because they knew that there was a new wave. Something big is happening. We’re going to get our independence and we’re going to get our rights. And the way they are depicted in the book is just insulting. Because to me, it was insulting to my mum, my aunts who grew up in that period, who had huge, big dreams. They were supported by the brothers, their parents, their husbands. So it doesn’t resonate with my Morocco, especially after that period.

Laura 22:49

And so I asked her, listeners, what did she think was happening with Slimani and her views?

Youssra 22:53

I think she’s heavily influenced by her own family, her own history. Her grandma is the one who inspired the character of Mathilde and she grew up in a heavily influenced background, culturally influenced background, by the French culture. When you go to a French school, you don’t study Moroccan history, you study French history. So everything you study is from a French perspective with a French scope. And the French scope was France Force Civilisatrice or France Civilising Power. That’s the narrative that every single one who goes to a French school is taught. I don’t even think it’s conscious is just the way you were brought up, and then you move to France. And that continues. Let’s not forget that Slimani has been appointed Macron’s representative for promoting French culture. She is very much a French writer. I don’t have the right to take away her Moroccan identity, but I can see it in her books. That’s the struggle for me. I wanted more balance.

Laura 24:03

And then we went on to talk about a few of the characters that felt problematic. The sister Selma, who is this sensual, gorgeous beauty, and I actually highlighted a passage with fresh eyes as I reread the book: ‘Selma radiated sensuality. Her eyes were as dark and shiny as the olives that Mouilala marinated in salt, her thick brows, her lush hair, the faint brown fuzz on her upper lip made her look like Carmen, a vision of Mediterranean sultriness a vibrant fever-dream of a brunette, capable of driving men wild.’ And I reread that I was like, ‘oh, yeah, that is quite over the top.’ And one of my complaints about Lullaby was that I thought that Slimani was going for an easy, sensationalist topic, and it does feel Youssra sharing some of her insight that there are certain cases throughout this book where she’s going more first sensation for depth or authenticity.

Kate 25:03

I think it is more nuanced than that, because we do know that as a writer Slimani is deeply concerned with the position of women in Moroccan society. And we see that Selma’s dreams of a future, of being able to choose her own romantic partner are dashed. And thanks to Amine fairly summarily, she’s married off to a character who doesn’t seem like a great option, although maybe he’s not as bad as we think. And all of this is intensified and exacerbated by her physical beauty. So, you know, it felt to me more like Selma was a symbol of every young Moroccan woman who wanted to choose her own future but was denied in this deeply repressive patriarchal society. That’s certainly the way that Slimani seems to be viewing it. But maybe what Youssra is showing us is that in her own decisions about how she’s chosen to dramatise it, perhaps she’s bringing the viewpoint of European feminism to bear when there seems to be a real debate, a real internal debate over how Moroccan women view their history and their situation.

Laura 26:05

And then there’s the other layer, which is that Slimani is basing her characters on family members. So if we’re assuming her aunt is the Selma character, how true to that real-life woman is this character, right? She might be slightly hamstrung by the actual family members she had.

Kate 26:25

Yes Slimani was asked about this in an excellent interview that she did with Words Without Borders, which, most of the time, I’ve been quoting things, that’s where it’s come from. And she said, ‘Of course, I use my own experience, but I also used what my grandmother told me about the life she had when she arrived in Morocco. I’m very lucky because my grandmother, my aunt, and my mother, were great storytellers. My grandmother loved Morocco. And by the end of her life, she had become a Moroccan woman. But she was also very critical of the country for its treatment of women, its poverty and its social classes. She was very critical of colonialism as well. She was a white French woman, that French people hated her because she betrayed them by doing something that was considered very scandalous, having sex with an Arab. It was accepted when it was a Frenchman having sex with an Arab woman, Frenchman conquered the country, after all, so they could conquer the women too. But it was different when it was a white woman having sex with my grandfather, who was dark skinned and very manly. And this tension that’s woven into this relationship between Mathilde and Amine, and Leïla Slimani, I think, is one of those writers who writes really, really, really well about sex. I found the ups and downs of their physical relationship and the way that that’s woven in, it never felt gratuitous, it always felt like it needed to be there. And she wrote about it well, and I found it believable, I have to say, I really bought into the very intense dynamic of that relationship between them, which could ebb from love and passion to anger, hatred, resentment, you know, it was all boiling away in there.

Laura 27:54

We haven’t talked about Omar though, the brother, who is given no space, as the family’s is one and only freedom fighter to voice why he wants French independence. And you make this point that the Moroccan history, the historical events that are swirling around this family are sort of pushed to the periphery, and they are, but that leaves you with an angry young man who just wants to be violennt, and Youssra spoke to how problematic that was because freedom fighters were not terrorists. They came from old cross-sections of society, and were asking for independence and yet Slimani paints Omar as an inarticulate violent, young man, and that’s our representative of the freedom movement.

Kate 28:39

Yes, I agree. Omar felt like a slightly exaggerated character. And he’s definitely there to ramp up the drama, when he’s on the page it’s always dangerous, you never quite know what’s going to happen.

Laura 28:52

I wanted to reassure Youssra in our talk – I don’t think I actually quite got to it – that the descriptions that are shared of Morocco in this book, I did read them as from Mathilde’s perspective, and therefore I read them as biased, colonial perspectives.

Kate 29:11

Yes, because one of her complaints is the way that the countryside is ugly, the people are dirty and uneducated and there’s no culture, there’s no refinement. That is the vision that you’re shown. And maybe if you have more context, you’re able to decode that more carefully and as you say, we’re seeing it from Mathilde’s perspective and Mathilde’s view is biased and blinkered. But to someone like Youssra reading about almost people she knows and places that she knows, I could see that that would be quite difficult. Come on, then what did your book club think? None of them are from Meknes I take it?

Laura 29:46

We all enjoyed it. I mean, it is that kind of book. I think that you can just get swept up in and there is enough drama in there more than you might expect for a novel inspired by a family memoir. So honestly, we had a fairly high-level discussion, praising it. And then at that point Youssra had already messaged me on Instagram. So we had already dug into some of her issues with the book. So I was able to elevate them to the book club and hear what they thought. And Youssra gave us that gift, really, I think, to be more critical of this book. So one of those books, where it’s really valuable to actually do a little research. And it’s all about dialogue.

Kate 30:28

Yeah, it’s what we love. It’s why we love to read because it’s in that debate and in that exchange of views and being challenged on some assumptions that for me lies the fun. It’s a nicely divisive book, it seems looking online. This review made me laugh. ‘Another example of misery-porn, hardship and boredom served up as entertainment. If it hadn’t been my book club’s choice this month, I would have saved myself the tedium of reading it past page 50. Quite a surprising view given I think you can say a lot of things about this book, but boring wouldn’t be one of them.

Laura 30:58

I’d love it if it was one of my book club members. Covertly posting on Goodreads [laughs]

Kate 31:03

[laughs] It almost felt like it was something that Andy might say in my book club.

Laura 31:07

Only if he was feeling contrary.

Kate 31:09

Yeah, exactly. The Book Doctor who reviews extensively it seems give it four stars. ‘It is a powerful, immersive and engaging novel about a family struggle against hostile surroundings. But it’s also a story that in an original way, sheds light on the origins of many of the most acute conflicts in our time. All the characters in this novel live in the land of others, settlers, natives, peasants and refugees. Women above all live in the country of men, and must constantly fight for their emancipation. Highly recommended. Amanda Jenkinson meanwhile gave it two stars. I found this novel strangely, lacklustre, and well, ordinary, surprising really, after Slimani’s earlier novels which I found original and compelling. Not that I didn’t enjoy this one. It’s a pleasant enough read, but it seemed to be missing something and I failed to fully engage with the characters and their plight. There were very few surprises in the book, and in fact, it was all pretty predictable. And although important themes are explored race class, interracial relationships, colonialism and decolonization, it all just felt flat somehow. Nevertheless, the book mostly held my attention, I wanted to see how it all panned out for the family. But a certain magic was definitely lacking.’

Kate 32:18

KF gave it four stars. This is not a book to read for entertainment, its characters and subject matter are too disturbing for that. But it is a book to read for an understanding of how different cultures can clash, and how what is unacceptable in one culture is a part of everyday life in another Slimani doesn’t hold back from describing violence, abuse or bloodshed, but it’s not done in a gratuitous way. It’s simply part of the lives of the characters, the country and the time the story is set. This book is not just a gripping insight into the country of others, but into the clashes of cultures that still form a part of our world.

Laura 32:50

The second book in the trilogy is out in French, if you wanted to challenge yourself, Kate.

Kate 32:56

Yeah, I actually read her book, Adèle in French. And even with my imperfect understanding of that language, it was a really powerful, compulsive read, but I would be the first to admit that most of the nuances were probably lost on me. So yeah, better wait for the English version I think, for this one. I had one more wants to read. Kay Radford gave it five stars: ‘Full disclosure, I loved Leïla Slimani his previous book Lullaby so I was thrilled to read her latest novel The Country of Others. I found this book heartbreakingly sad at times the depiction of life for women in a country full of traditions and ideas that mean they have no say and virtually no freedom seems alien to a modern-day reader. Mathilde’s desperate search for happiness and fulfilment is so movingly portrayed. Amine is at times a modern thinker, especially when it comes to the education of his daughter and his farming practices. But then he contradicts this by his attitude to his younger sister who was forced into a marriage against her will. The book is set against the backdrop of Morocco fighting for independence from France and I found this fascinating as it’s a subject I know virtually nothing about, and it made me want to find out more. I love this book, and giving it only five stars seems inadequate for what is, in my opinion, fabulous masterly writing, I can’t wait to read Leïla Slimani’s next book, and the one after too.

Kate 34:09

I love Leïla Slimani’s writing. I did love this book, although I’m fascinated by the knowledge that Youssra brought to my reading of it. And the debate that it’s clearly going to stimulate in France and in Morocco, or has done already, which will be ongoing as the subsequent volumes come out. But you know, mainly I just think ‘what a writer’, she is incapable of writing a boring sentence. I love that about her. I love her ambition. I love her fearlessness. You know, she’s not afraid. Many people faced with the kind of backlash and criticism that I think fairly regularly comes her way would hesitate and draw back and I’m in awe of her bravery and fearlessness and conviction that she has, all of which for me, made it a very worthy read and I love it for book club. I think it’s such an interesting one to discuss.

Laura 34:59

I think that’s absolutely right, it’s an interesting one to discuss. It’s one of those books where you should be aware of your own ignorance and your own bias and try to counteract that. If you don’t have Youssra reaching out to you, I think there are other ways to do that. But what Slimani has done, perhaps, in being who she is and being such a break-through talent, she has opened up more space for more diverse voices to come through and tell their versions of Morocco and to bring more richness to readers like us.

Kate 35:34

Here are some more recommendations inspired by The Country of Others by Leïla Slimani. And of course, having got her we couldn’t resist asking Youssra for hers.

Youssra 35:42

One of my favourite authors is Fouad Laroui, who is Moroccan but he lives in Amsterdam. He grew up in Morocco studied in Morocco, he went to French school, but he comes from very humble background. He worked as an engineer in Morocco. And his accounts are hilarious, but very on point, very on point about Moroccan culture. Unfortunately, he writes in French, most of these books are not translated into English. This one in particular is called Une année chez les français, A Year with the French. It’s his account when he went to study at a French institution, it’s inspired by him, but it’s a fiction and the way he talks about the casual racism, it was post independence out in the late ’60s, early ’70s. It’s such a wonderful account about the French who stayed in Morocco who were running the school, but his classmates – an absolutely lovely book. I absolutely love that book. And I wish, I really wish that book was translated into English because it’s such a good book. It’s called Une année chez les français by Fouad Laroui.

Youssra 36:44

But my Moroccan go-to writer, if you want to, is called Leïla Lalami. She is Moroccan and writes in English, hooray! Born in Morocco, she lives in the US, she teaches at an American university. And she wrote a wonderful book called The Moor’s Account. It’s the story of a young Moroccan merchant in the 16th century. He’d been enslaved. So it’s inspired from a real character who had been enslaved and then sent to the mission to discover the Americans. So this man who is called Mustafa Zamora was the first African-Arab to set foot in the Americas. And of this mission, only three people survive. Historical accounts talk about the two Spaniards, but they discard his own accounts. So Leïla Lalami did a very fantastic search, meaning it’s very heavily researched book and she found his own accounts about his adventure, his encounter with the Native Americans, with his master as well, and the army captains. And she gave him his voice back. It’s just a fantastic book. It’s been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2015, and finalist for the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction so it’s been highly acclaimed. So yeah, when I want to read Moroccans, I read Leïla Lalami or Fouad Laroui.

Laura 38:04

I wanted to recommend This Blinding Absence of Light by Tahar Ben Jalloun, it is actually Youssra recommendation, but one she gave to me personally over Instagram after we’d been going back and forth. In Youssra’s words ‘it depicts the harrowing journey of a Moroccan prisoner incarcerated in the infamous Tazmamart prison, secretly built for political dissidents. It’s beautifully written and quite faithful to the account of the former prisoner.’ Now, Kate, I mean, we’ve been saying throughout this, that we’ve really felt our ignorance of Moroccan history, I still feel that ignorance, what we should seek out is probably a history to really ground our knowledge. But this book is a sliver of a lived historical experience, where after a failed revolution against the King, I think this was in the 1970s, a whole swathe of serving officers in the army were imprisoned, and they were imprisoned underground in these small cells with barely any light coming through. And they could not stand up. And they were not treated in any way in fair conditions. And so when they finally emerged decades later, they had actually lost almost like a foot in height. And this sounds so harrowing, and I said to Youssra like, ‘I can’t read that’, but it’s written in a very economical way. So it’s disturbing, but it’s not distressing as you’re reading. It’s more that it sticks with you. And you think about, you know, these terrifying human rights abuses that have happened in the past and that very likely continue to happen in all sorts of places around the world. It has something of the – I don’t want to say Kafkaesque, but there is something of that like Sisyphean, like what are you left with when life is not worth living? And yet you persevere. What happens to a human being what happens to the way they think and how do they sustain themselves in those impossible conditions?

Kate 39:54

Yeah, something about resilience, which it’s always good to examine. My book recommendation was a bit of a serendipitous find in my little free library. It’s called All Men Want to Know. And it’s by a French writer called Nina Bouraoui. She is actually French Algerian. She has an Algerian father and a French mother. So like Slimani, she spent most of her youth in her home country, in her case, Algeria, and then she moved to France. It’s autofiction, that blend of memoir and fiction that I always tend to love, actually. And it explores that sense of placelessness, a sense of not belonging quite to either country. And as Slimani has said to people who are in that position, they have to create their own identities as they go along. And for Bouraoui, it was doubly problematic because she’s gay. And this isn’t something that she was able to express in her home country where I imagined perhaps similarly to Morocco, there were fairly strict rules about how women could conduct themselves, and like Slimani she’s from an affluent middle class family, her parents worked in the oil industry, but her mother is raped. And as a result, they leave Algeria, and they go to live in France. It’s such an interesting book. And a really lovely book, actually, it’s not long, and it flips between her childhood in Algeria and her feelings about this childhood, which reminded me a bit of the way Françoise Sagan writes in Bonjour Tristesse with this quite economical language, but when you sort of feel the sun on your skin, and you smell the wild thyme in the air, and it gives you this real sense of her experience, her memories of this place, contrasted with her life in contemporary Paris, where she’s going to nightclubs to try and meet women and exploring that side of her identity. And then every so often in quite an understated way, these devastating glimpses into some very difficult things that her family were experiencing, different members of her family were experiencing and how that impacted on all of them. So it’s a really interesting book, it won the English Pen award. It’s apparently been an international bestseller. Sarah Waters calls it ‘intense, gorgeous, troubling and seductive’. And I had never heard of it. I was very happy to read it. I really enjoyed it. And I think it would be a really interesting one for book club.

Laura 42:17

I have one final recommendation to throw in because I set off for the public library, as ever, inspired from our discussion with Youssra a few days ago, and I picked up Year of the Elephant: A Moroccan Woman’s Journey towards Independence and other stories. And it’s a short story collection, published in 1989 by a female Moroccan writer. I started to read the title story. And, you know, it was quite dramatic how different it was to be inside the head and perspective of a woman who has grown up in Morocco. You know, that contrast with Mathilde’s perspective. Anyway, I’ve only just started the main story about this woman who returns to her hometown having been divorced after 20 years of marriage, because actually, she’s not able to blend in with the modern life that he actually wants. She’s from a more traditional upbringing and hasn’t made that leap with him and mentioned it to Youssra and she said ‘yeah, I remember studying that in school.’ So that’s by Lila Abouzeid and seems really great. I’m gonna keep going.

Kate 43:20

Well, we will put all those titles and spellings, crucially, in the show notes so that you can find them.

Kate 43:30

That’s nearly it for his episode. Our book recommendations were Une année chez les français by Fouad Laroui, and The Moor’s Account by Leïla Lalami, This Blinding Absence of Light by Taha Ben Jalloun, All Men Want to Know by Nina Buraoui, and Year of the Elephant by Leila Abouzeid. The audio book of The Country of Others is published by Faber & Faber and available from audio book retailers.

Kate 43:54

We loved hearing from our book club and from Youssra on The Country of Others, but what do you think? Did you know that each podcast episode has a dedicated page on our website where you can find full details about all the books we’ve recommended, a transcript and a comment section. Scroll down to the link in the show notes or head over to thebookclubreview.co.uk and let us know your thoughts, comments there do go straight to our inboxes and we will answer them we would love to hear from you. Let’s keep the discussion going.

Kate 44:20

Coming up. We’re diving into the world of Fitzcarraldo, the elegant blue and white books that are frequently winning awards. We talked to publisher Jacques Testard and discuss our favourites from the Fitzcarraldo list. If you’re looking to expand your reading horizons. Don’t miss that show. It’s coming soon. If you’re heading over to the website, you’ll also find our complete archive of over 100 shows to browse through, covering books from page turners, like Where the Crawdads Sing to our deep dive into long reads with Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain or check out any of our bookshelf episodes for a stack of book recommendations and let us help you figure out your next read.

Kate 44:53

You can also follow us on Instagram or Facebook at Book Club Review podcast on Twitter @bookclubrvwpod or email us at thebookclubreview@gmail.com This episode was produced and edited by Me, Kate Slotover. Do subscribe to us. And you can support us by taking a minute to rate and review the show which helps other listeners find us but not as much as you just telling your bookish friends about us. So if you’ve enjoyed the show, please do spread the word. But for now, thanks for listening and happy reading.

Comments

Any thoughts on this epsisode? Let us know here. What did you think about Leïla Slimani’s The Country of Others, or have you read any of the books we discussed? What book would you recommend?